Does Strength Training Help Improve Your Flexibility?

March 25, 2009

Recent research has look at this question with interesting results. Most often people use passive stretching as the main method to try and increase flexibility in particular muscle groups. Passive stretching has been shown to improve flexibility if consistently done over a long period of time. The question is can you combine your flexibility training into a strength program? And if so what movements improve flexibility?

An article posted in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research in May of 2008 titled “Influence of Strength Training on Adult Women’s Flexibility” (Monteiro, Simao, et.al) looked at how 10 weeks of strength training influenced flexibility in sedentary middle-aged women. The exercises used in the study included bench press(free-weight), Smith squat machine, anterior wide grip lat pull-down, 45-degree leg press, 30-degree inclined bench press, hack squat machine, and abdominal crunches. The average age of the women in the study was 37 years + 1.7 years. This particular study demonstrated that after training for 10 weeks and going through three (3) circuits of 8 to 12 repetitions of the seven (7) exercises listed above, that significant improvements in range of motion occurred with the following movements; hip flexion and extension, trunk flexion and extension and shoulder horizontal adduction. The areas that did not improve range of motion where elbow and knee flexion. While this study did show that strength training can improve flexibility in sedentary women, the next question is are there strength exercise movements that can improve flexibility in rowers? To my knowledge there are no studies that have looked at rowers and how strength training would influence flexibility. The above study did demonstrate increased hip flexion, which is critical in rowing, and so the use of the squat machines did increase hip flexion range of motion. What the above study did not look at is how hamstring mobility was affected by the above strength training program. This would have a lot of relevance to an effective rowing stroke.

From my own coaching experience I believe that there are several key lifting movements that will certainly increase flexibility in rowers in a positive way, if they are done properly. These strength movements include the “overhead squat” and “straight-leg dead lift”. Both of these lifts require a higher level of body control and awareness and people who attempt these positions should try and get a professional to look to make sure proper technique is being used. In general these open movements are better than strength training machines used in the above study. This is because the neural input needed from the athlete is greater with open movements, and the carry-over is probably better as well.

Straight Leg Dead Lift

Over Head Squat

“Other research on flexibility training has focused on developing effective strategies to increase the range of motion and identifying the factors that limit flexibility. There has been some disagreement over whether one’s limitation’s in flexibility is really from the inability to completely relax the involved muscles. Studies have shown that range of motion is much greater when a person is completely anesthetized, Walsh (1992) suggested that the inability to relax is a major limitation in the range of motion about a joint.” (Enoka, 2002).

Often we hear our coaches tell us how important it is to relax in the boat of no the erg which will help to produce a long and powerful stroke. Relaxation allows for a more complete range of motion through all the joint movement in the rowing stroke. Training movements repeatedly help to improve relaxation of a motion. There are few sports that require as much flexibility as rowing (Olympic lifting and Gymnastics), so flexibility is a critical component to effective and powerful stroke rowing strokes.

**When strength training it is advised that you are under the supervision of a trained professional to assist with proper technique to reduce injury risk.

Have a Great Training Day!

Coach Kaehler

References;

Enoka, Roger M. Neuromechanics of Human Movement. New York: Human Kinetics, 2001.

“Influence of Strength Training on Adult Womens flexibility.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 22 (3), 2008: 672-77.

Hamstrings: Stretching, Flexibility and Strength

January 20, 2009

See Below

Improving your Hamstring Flexibility

January 2, 2011

By Bob Kaehler MSPT,CSCS

Have you ever complained that your hamstrings always feel tight? No matter how much you stretch your hamstrings, they never seem to become more flexible?

Flexibility is a key factor in allowing you to get into the best body position at the catch, and in achieving a long, strong, and powerful rowing stroke. Tight hamstrings limit your ability to achieve this ideal body position. Static and dynamic stretching are two effective methods used to improve your flexibility. Long term changes to flexibility require consistent effort. The hamstrings are no exception.

Static stretching has long been used as a way to increase flexibility in muscles, and improve range of motion in joints. This type of stretching is done without movement (i.e. you remain still). The force or pressure is applied to the area being stretched by an outside force, such as a wall, strap or another person.

Studies have shown that the biggest improvements in ranges of motion occur when the end range stretch position is held for longer periods of time (10+ seconds, o r longer). The stretch position should be repeated multiple times (5-10) for greater results. For athletes looking to actually get a permanent change in their flexibility, consistency becomes a key factor. Stretching should be done every day, and if possible, several times a day for even greater results.

Recent studies also confirm that static stretching does reduce your explosive strength immediately following the stretching period (up to an hour or so). Therefore this method is best used after training sessions, not before. A simple, yet effective, method of statically stretching hamstrings involves using a door frame. Simply lie on your back next to doorway with your feet facing the opening. Slide the non-stretching leg through the doorway, then place the stretch side foot up onto the molding. Extend the knee joint of the leg being stretched so it becomes straight. You will probably need to adjust the distance of your hips from the wall to get the proper stretch tension. Ensure your tail bone does not come off the floor once you are in the appropriate stretch position.

Another approach to stretching is dynamic. Dynamic stretching is an active method where you provide the energy (i.e. you move) to produce the desired stretch. Ensure, however, that you do not exceed your normal end range for the movement otherwise it becomes a ballistic stretch. Dynamic stretches usually mimic the same sporting form that you are about to perform. To produce a good hamstring stretch, simply do a quick body-over pause (1-2 second hold), whether you are on the water or on an erg. Keep your low back in a firm upright position with the spine as straight as possible. Slumping at the low back eliminates much of the stretch on the hamstrings, so be aware of your posture. You should feel a good stretch in the back of the knees (bottom of the hamstrings) when you are in the body over pause position. If you do not you either have very good hamstring mobility or you are slumping in your low back. The point of dynamic stretching is to warm-up your body before training and racing; not to force your range of motion beyond your natural limits. Practice this form of stretching on a regular basis before adding it to your regular pre-race warm-up routine.

Dynamic stretching is ideal for warming-up muscles and joints prior to training sessions and racing. Its purpose is to prepare the tissue to properly handle the stresses of the activity. Static stretching, on the other hand, is ideal for making permanent changes (i.e. increasing) range of motion, and is best done separate from training and racing sessions.

With proper technique, combining both static and dynamic stretches into your training program is an effective way to prepare for training properly, to reduce your risk of injury, and to improve your baseline flexibility.

ARTICLE 2

Hamstrings: Stretching, Flexibility and Strength

By Bob Kaehler MSPT,CSCS

Rowers and other endurance athletes are often unsure if they have optimal flexibility in their hamstrings. Also, the question of which stretches are best, and what methods are the most effective to improve hamstring mobility? Good hamstring range of motion does allow for better rowing and running technique, while inflexibility in the hamstrings can lead to increased low and mid back stress. Below we will discuss two methods of stretching commonly used; static and ballistic techniques. Both methods are commonly used to improve musculoskeletal flexibility with endurance athletes.

The most common method used to try and improve muscle flexibility is “static” stretching. A typical static stretch is held for 10 seconds to 30 seconds once the stretch position is reached. Ballistic stretching also called “bounce” stretching, is done by bouncing in and out of the stretch position in quick succession multiple times.

Several recent studies looked at how static and/or ballistic stretching methods effected flexibility and strength. One of the studies looked at the effect of duration (hold time) of static stretching on muscle strength endurance, while the other compared flexibility and strength changes following the use of static and ballistic stretching methods.

The first study compared how the length of static stretching time effected muscle force production in the hamstring muscles. There were three groups in this study, the control group – no stretch, a 30-second hold group, and a 60-second hold group. The results of this study demonstrated that the control group and 30-second hold group had no loss in hamstring strength, while the 60-second hold group had a significant loss of strength following the stretching protocol. Strength was tested with 45 degree leg press.

The second study looked at the difference between static and ballistic stretching methods on flexibility and strength. Static holds were for 30 seconds, and were repeated several times, while the ballistic stretching was done by “bobbing’ for a 1:1 second cycles for one (1) minute. The results of the study showed that the static stretching produced a greater increase in flexibility when compared to the ballistic stretching. However strength results were significantly reduced for the static stretching group while the ballistic stretching group had no loss in strength. The conclusion of this study recommended that static stretching of 30 -seconds should not be done just prior to an athletic event or race, while ballistic stretching would be much less likely to reduce maximal strength.

Hamstring Stretching

Below are pictures of some stretching methods used to improve hamstring mobility.

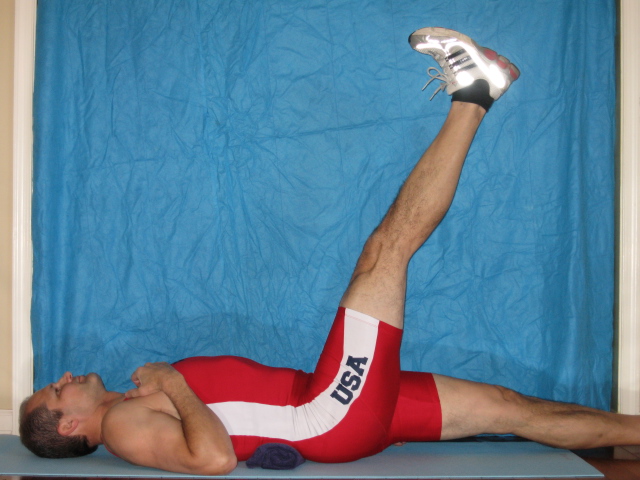

Straight leg raise position, 90 degrees (vertical) is good general range.

In order to get the body over in the rowing stroke and have the back in an ideal position one needs to have good flexibility in the hamstrings. Also, to get into a good catch position hamstring mobility is also important. Stretching the hamstrings before,during and after training can help keep this important muscle group mobile. The above picture shows a dynamic stretch to the hamstrings. Here we are using the hip flexors, abdominal muscles, and quads to stretch out the hamstrings.

Active-static hamstring stretch

Here we use the quadriceps muscles to stretch the hamstrings. Ideal hold length is from 10 to 30 seconds. Repetitions will vary based on flexibility. Note a towel is rolled up under the low spine to eliminate low back movement when stretching the hamstrings.

Above is a typical toe touch stretch. This technique stretches both the thoracic and lumbar spine as well as the hamstrings. Those who have great spine flexibility might not get much of a stretch in the hamstrings. This method is not as effective as the straight leg dead lift position below in stretching the hamstrings.

Active-static hamstring stretch

Optimum Performance and the Use of Caffeine

January 11, 2009

Do you grab a quick caffeinated beverage before racing, or chug a caffeinated sports drink during your workout? Many athletes believe consuming a shot or two of caffeine is an ideal way to get that quick boost of energy in the quest for better performance. However the effects of caffeine on your endurance training may not be giving you the results you are looking for. Of course, many people use caffeine throughout their day to help stimulate them during daily activities and energize them during their workouts. Understanding the effects that caffeine has on a body is important in deciding whether or not to use caffeine as part of your training program.

Caffeine is actually a toxic stimulant found in nature. Although it revs the body up, it provides zero in terms of energy. After ingesting caffeine, your body automatically begins the process of metabolizing (getting rid of) it. This metabolic activity actually costs you energy and takes it from your storage of nutrients. Therefore a stimulant like caffeine triggers an abnormal “speeding up” reaction to begin eliminating it. This “speeding up” is the caffeine buzz you feel, but in actuality it is depleting your body of necessary energy and nutrients.

Not only does the process of metabolizing caffeine use up energy, it has diuretic effects (fluid loss) as the body tries to clear it from your system. This creates a negative water balance in your body, leading you to urinate more. Coupled with the elevated heart rate usually caused by caffeine, the diuretic effect could lead to over-stimulation of your body, potentially leading to dehydration in people already pushed to their physical limits. During this process of elimination we can be fooled into thinking that the stimulant is an energy value, when really it is an energy cost.

A recent article published in The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, titled “Caffeine and Endurance Performance”, by Matthew S. Ganio, et al., is a systematic review of 21 different studies which measured performance with a time-trial test. They looked at endurance events that were at least five (5) minutes or longer, such as cycling, running, etc. The authors of this study concluded that although the performance improvements were varied among the studies researched, they found that factors including timing, ingestion mode/vehicle, and subject habituation may have influenced study results.

One significant recommendation Ganio, et al., made from this review was that endurance athletes abstain from caffeine use at least seven (7) days before competition to maximize its ergogenic (boosting) effect. Also, it was noted by Ganio, et al. that if caffeine is used for an ergogenic effect, it should be ingested within 60 minutes or less of competition or training. The amount of caffeine commonly shown to improve endurance performance is between 3 and 6 mg. per kg-1 body mass. The caffeine benefit was equally effective when consumed with a carbohydrate solution, gum, or water alone, however coffee was noted to not to be as effective a caffeine source. When caffeine is used on a regular basis, the ergogenic effect is not as great, compared to using it sporadically or not at all.

Overall, chronic use of caffeine appears to have far less effective results in time-trial testing, and appears to cost the body energy and nutrients in elimination from the body on a daily basis. However, should an athlete decide that caffeine use is beneficial, it would make sense to follow the guidelines for amounts ingested and limit use during time trials spaced seven days or more apart, prior to race day. Determining the best use of caffeine, if any, is a personal decision best made with the advice of your physician and coach.

Before grabbing that caffeinated sports drink, consider the effects of caffeine on your body. Because of the generally negative effect that metabolizing caffeine has on a body, Coach Kaehler does not advocate the use of caffeine as a regular part of a training program. Instead, he believes that a well balanced, specially designed training and nutrition program is much more effective for achieving the maximum performance results desired on race day.

Coach Kaehler has posted this for informational purposes only, and that the use of caffeine for performance enhancement is a personal preference. It should be noted, however, that he does not recommend the use of caffeine for the clients he trains.